- 06/05/2016

- Media Releases

Cambridge steel recycling advocate joins external panel advising Liberty House in bid for Tata UK

The head of the Cambridge university team, whose research has demonstrated a powerful case for a new, recycling-based, British steel industry, has joined the external panel of experts advising Liberty House in its bid to buy Tata Steel UK.

Professor Julian Allwood, the University of Cambridge Professor of Engineering and the Environment, will advise Liberty as it sets out its proposition that melting scrap in electric arc furnaces should become the principal method for making liquid steel in the UK and sustaining many thousands of jobs.

His team’s recently-published report, drawn from six years of Government-funded research, concluded that the world now has more blast furnaces than it will ever need again. It says it will be difficult for those in Britain to compete in a world with excess capacity, particularly with the newest and most modern plants being in China, and the likelihood that India will also expand its steel-making capacity with new blast furnaces in light of their plentiful supply of local iron ore and coal.

The document entitled ‘A bright future for UK steel’ argues instead for making liquid steel in the UK from low-cost, and increasingly abundant, domestic scrap, most of which is currently exported for melting abroad. The Cambridge team’s research found that the supply of UK scrap is projected to double from 10m to 20m tonnes a year over the next 10 – 15 years.

According to the report, new steel-making technology, combined with Britain’s expertise in materials science, will allow a greater range of advanced products – including automotive and aircraft components – to be made from recycled steel. In addition it maintains that greater integration of the manufacturing supply chain will help make the steel sector more efficient, competitive and secure.

Liberty House executive chairman, Sanjeev Gupta, said he was very pleased Professor Allwood had agreed to advise the bid team: He added: “The conclusions of the Cambridge team match our own industry analysis and our GREEN STEEL strategy very closely and we believe their work will be hugely valuable to us in developing and refining our business model for the sector.

“Making liquid steel from scrap involves half the cost and a third of the carbon footprint of the equivalent blast furnace method of production, so making the transition over time to recycling will give us a greener and far more competitive industry.”

However he added: “While we firmly believe the future of UK steel is in recycling, we are very conscious that we need to protect the high-end customer base in automotive and other applications, so we will work with them to forge a transition plan that meets their expectations.”

He said the Cambridge report’s conclusions also accord with Liberty’s strategy to integrate the steel industry all the way from renewable energy generation, though liquid steel production and into the down-stream manufacture of advanced steel products and components.

“By integrating the industry’s supply chain, and by using British expertise and innovation to create efficiencies and higher-value steel products, we can create a very promising future,” the Liberty chairman said.

Liberty, through the Gupta Family Group Alliance, is currently investing in the development of renewable energy to power its steel operations.

Professor Allwood said: “It is very appealing to be involved in such a major development within British industry and to put our research to work in addressing a very serious problem facing the steel sector here.”

Prior to developing an academic career, Professor Allwood worked for 10 years at aluminium giants, Alcoa. His academic work has focused on the need to reduce industrial carbon emissions by making less new material. His book “Sustainable Materials: with both eyes open” was listed by Bill Gates as “one of the best six books I read in 2015.”

Professor Allwood is Chairman of the metal forming branch of the International Academy of Production Engineering (CIRP) and an Honorary Fellow of the UK’s Institution of Materials, Minerals and Mining.

The summary report: “A bright future for UK steel” can be found at: http://www.cam.ac.uk/research/news/uk-steel-can-survive-if-it-transforms-itself-say-researchers

Key points arising from the on-going programme of publicly-funded research behind the report are:

- The supply of steel for recycling in the UK is going to double in the next 10-15 years. We buy around 20m tonnes of steel in new goods in the UK each year, to add to our stock of ~800m tonnes of steel in use. We currently discard around 10m tonnes a year, 90% of which is sent for recycling; about two thirds exported. However, steel goods only last for 35-40 years on average, and developed economies’ stocks of steel saturate at around 12 tonnes per person – so we can have high confidence that, in the next 10-15 years, UK discards will rise to about 20m tonnes per annum to match annual purchasing.

- The CO2e emissions from making liquid steel from scrap in an electric arc furnace are around one third of those from making it from iron ore in a blast furnace. The details of these figures are sensitive to the amount of scrap used in the blast furnace, and the amount of blast furnace iron used to dilute scrap in the electric arc furnace. But most importantly, these numbers assume that electricity for the Electric Arc Furnace is supplied from coal. Lower emissions electricity supply improves the emissions benefit of the electric arc furnace route even further.

- Recycling in the UK today mainly produces lower quality steel but there is no fundamental reason why we cannot produce high-quality steel from scrap in electric arc furnaces. The two key contaminants of scrap are copper (from motors and wiring in cars and equipment) and tin (from food packaging). We could already manage scrap supplies much better to reduce these problems – as happens in the US – and we could use UK strengths in materials innovation to develop and export new technologies to remove the problem.

- The incumbent steel industry is highly consolidated and makes intermediate products only, but there is a rich opportunity for integration downstream. Around a half of all steel made today is wasted: a quarter of it is cut off in manufacturing and never enters a product; most products are significantly over-built and could use at least a third less steel. The opportunity for innovation in the use of steel is inhibited by today’s fragmented supply chains, but the UK has strengths in the downstream use of steel which could be connected to efficient upstream steel production.

Latest News

View All Media Releases

Media Releases

LIBERTY appoints Thomas Gangl as CEO of its European business

LIBERTY Steel Group (“LIBERTY”) has appointed international sustainability leader Thomas Gangl as the Chief Executive Officer of its European business,...

View Media Releases

Media Releases

LIBERTY announces UK strategic steel plan after signing new creditor framework agreement

LIBERTY today announces the strategic plan for its UK steel assets after signing a new framework agreement (“the framework”) with its major creditors. The new framework comes after...

View Media Releases

Media Releases

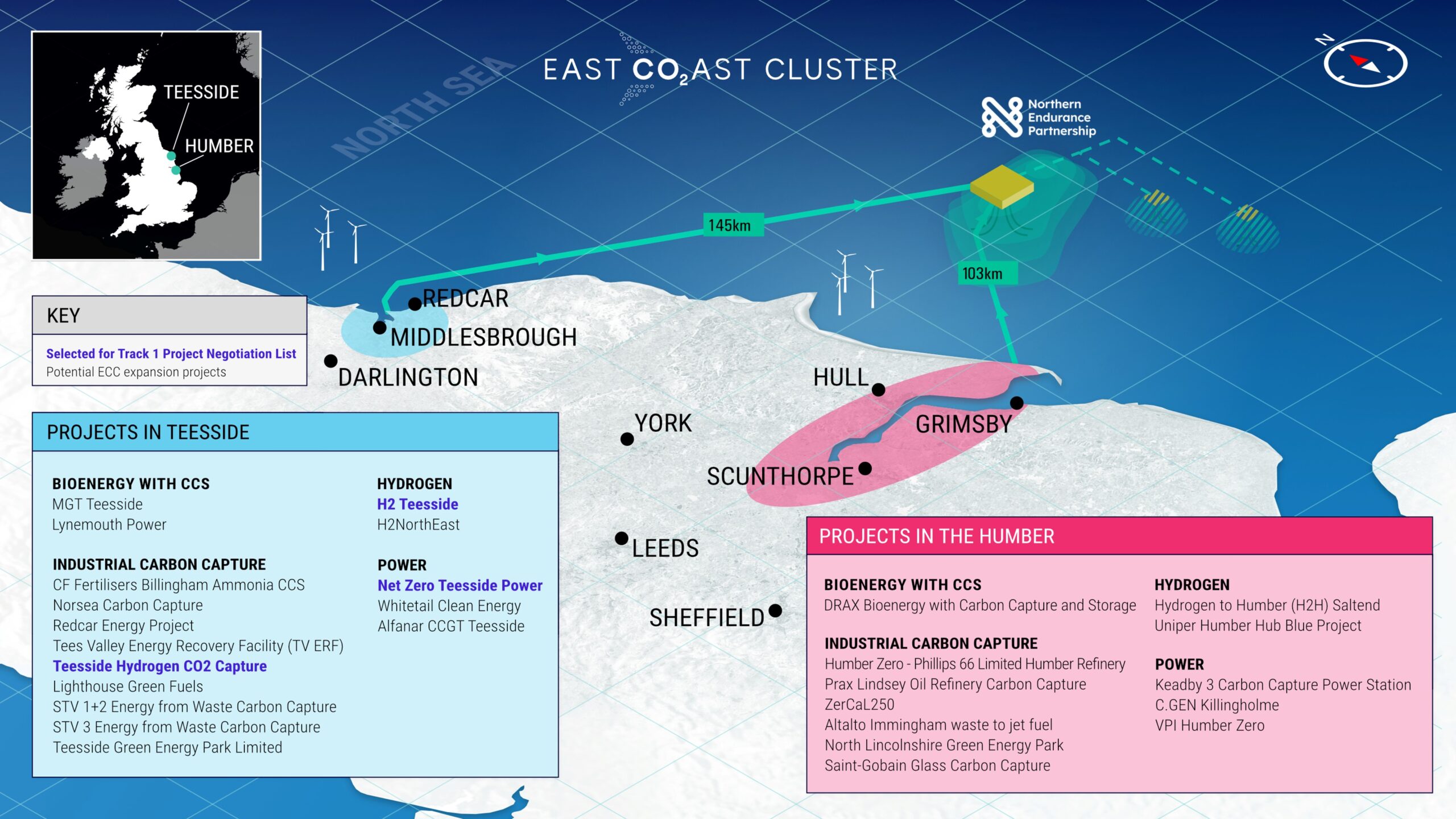

LIBERTY Steel selected for major UK carbon capture pipeline contract

LIBERTY Steel today announces that its Hartlepool pipes division has been selected for a major contract to supply pipelines to...

View Media Releases

Media Releases

GFG Alliance Signs Landmark Deals In Whyalla

Agreement on hydrogen and memorandum of understanding with Santos for gas Landmark Hydrogen Offtake agreement with South Australian Government MOU...

View